There is a genuinely jaw-dropping moment at the heart of this revelatory exhibition dedicated to the High Renaissance master Michelangelo Buonarroti and his brilliant acolyte, the Venetian Sebastiano del Piombo.

The show is arranged over six rooms that follow Michelangelo and Sebastiano from their first meeting in 1511, through their joint development of a Roman style in tandem with Raphael, and their eventual separation.

By halfway round you’ll be dizzy with the rediscovery of Sebastiano’s forgotten genius in big, ambitious oils such as the The Raising Of Lazarus.

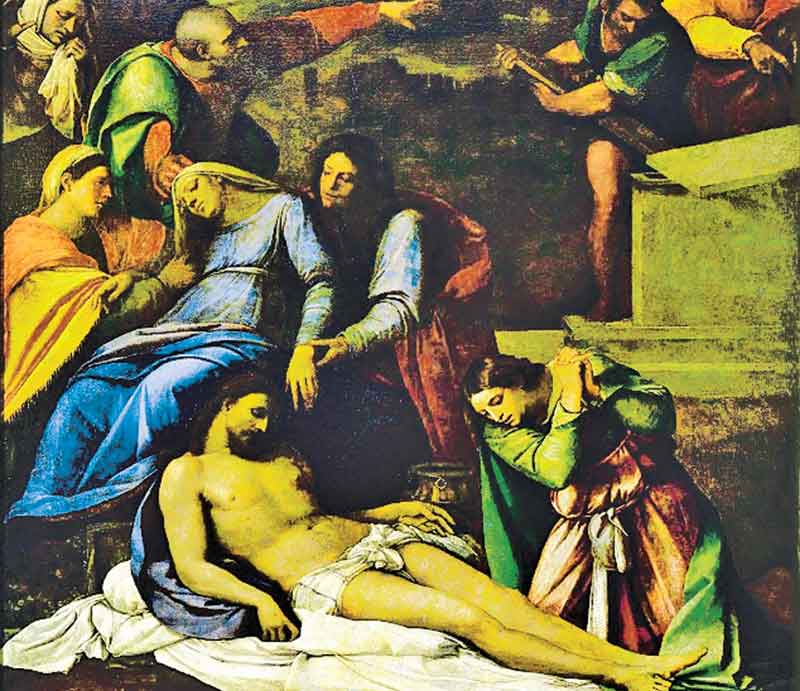

On the next wall Sebastiano’s Lamentation Over The Dead Christ, from the Hermitage museum in St Petersburg, joins Christ’s Descent Into Limbo, from the Prado in Madrid, for the first time since they were separated in 1646 (a 17th-century copy of Christ Appearing To The Apostles completes the broken-up triptych).

Then you come to Room Four’s wide doorway. Inside, two life-size Michelangelo sculptures of The Risen Christ hover at head height, bathed in an apparently heavenly glow.

The one at the back is a plaster copy of the original that never leaves Rome’s church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. In the Eternal City, Catholic decency requires that Christ wears a bronze loincloth, but here the muscular saviour, Michelangelo’s fully realised synthesis of Christianity and the classical world, steps forward with unfettered loins.

Before him, miraculously, stands another Risen Christ, known as the Giustiniani - the original marble version abandoned when Michelangelo discovered a vein of dark stone as he carved the face. The pairing knocks you back on your feet.

There are more wonders and some surprises, including a computer-mapped facsimile of Sebastiano’s frescoes of The Transfiguration and Flagellation Of Christ (drawn by Michelangelo) in the Borgherini chapel. But the pairing of the Risen Christs is a world first.

Gazing upon the finished Risen Christ in 1521 - harder today in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, where visitors are obliged to feed coins into a meter for the spotlight - an awestruck Sebastiano said: ‘One knee is worth all Rome.’

The two men - Michelangelo the Tuscan country boy born in 1475 who became the greatest artist who ever lived; Sebastiano, the lute-playing Venetian ten years his junior who swaggered into Rome in 1511 - became remarkably close.

Sebastiano was invited on to the scaffold for an on-the-spot view of Michelangelo’s progress on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and in moving letters displayed on the gallery wall Sebastiano writes to Michelangelo of ‘the love I have of you’.

Yet it was not love that sealed the partnership but bitter rivalry with Raphael, a painter Michelangelo damned for stealing figures from the Sistine Chapel and placing them in the Stanze, or Raphael Rooms, the fabulous decorated Vatican staterooms two floors above the Sistine.

Michelangelo complained of Raphael: ‘Everything he did in art he got from me.’ Unfortunately, everything Raphael did tended to be painted in oil with a facility that Michelangelo - master of fresco, sculpture and architecture - lacked. Sebastiano had that facility in spades, as a smaller oil, Judith (or Salome?), of a woman in luminous blue silk, reveals.

In return, Michelangelo offered an unparalleled ability with the human form that gave the world David, The Creation Of Adam and the heart-breaking Pietà, completed when he was only 24, that stands in St Peter’s and is represented here in plaster but is no less powerful.

The artists were different in temperament and approach, as two pictures in the show illustrate.

Sebastiano’s unfinished The Judgement Of Solomon bears the marks of a man willing to improvise. Michelangelo’s The Entombment, also unfinished, is heavily plotted, sculptural in its intensity.

But their collaboration worked, nowhere more so than in Sebastiano’s The Raising Of Lazarus, the very first entry into the National Gallery’s collection, acquired in 1824. Michelangelo took on Lazarus and the workmen around him; Sebastiano took on Christ and the onlookers repelled by the stench of decay.

Lazarus, face still grimy from the tomb and leg cocked to flex off rigor mortis, moves his right arm across his body to push away the winding sheet, eye fixed on the Christ who has delivered him.

It is both an astonishing and intensely moving painting, and mattered all the more to Sebastiano and Michelangelo because, like Raphael’s Transfiguration, it had been commissioned for the cathedral at Narbonne.

Why the great enmity with Raphael? Simply the resentment of men jostling for the Pope’s favour? A feud between one homosexual artist and another so vigorously heterosexual that his death was allegedly caused by a night of too much sex?

We will never know if Sebastiano was Michelangelo’s lover but they lived in each other’s pockets. Sebastiano’s Lamentation Over The Dead Christ is one of the most striking images in the show and features the first nocturnal landscape.

Unlike Michelangelo’s Pietà, here Mary, her eyes to the heavens, sits apart from her dead son.

But go round the back and you’ll find Michelangelo has, in a few sketched lines on the wood-wormed poplar boards, been working on figures for the Sistine ceiling.

IT’S A FACT

In The Agony And The Ecstasy, with Charlton Heston, the ‘paint’ dripping into Michelangelo’s mouth from the Sistine ceiling is really chocolate pudding.

The friendship of more than 25 years ended in the Sistine Chapel, when Michelangelo’s first attempt at The Last Judgement, encouraged by Sebastiano, ran into trouble.

When Sebastiano died in 1547, Michelangelo - hurt, old and perhaps a little cranky by then - dismissed him as a ‘lazy artist’.

The claim was manifestly untrue, as this remarkable show, bringing major works together in celebration of their respect and love for each other, proves.

But you might want to go to Room Four first.

It’s a bold call to make in March, of course, but Madonnas & Miracles is surely the exhibition of the year.

Based on a holy trinity of solid scholarship, thoughtful installation and fascinating exhibits, it also overturns preconceptions about the Renaissance. Not bad for a show that’s free to enter.

In the exhibition we’re shown that the Renaissance wasn’t quite the era of worldliness and secularisation that many today suggest - life was still marked by profoundly observed religious devotion. - dailymail.co.uk

Add new comment