From time to time, spiritualists and thinkers emerge in the society pronouncing the value of existence and the essence of living conditions via religious visions. These religious visions are manifold. Some are based on the views of other previous religious teachers, and some are based on new interpretations formulated in modernistic outlooks.

The name of such a spiritualist was known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh or more known as Osho (1931 – 1990).

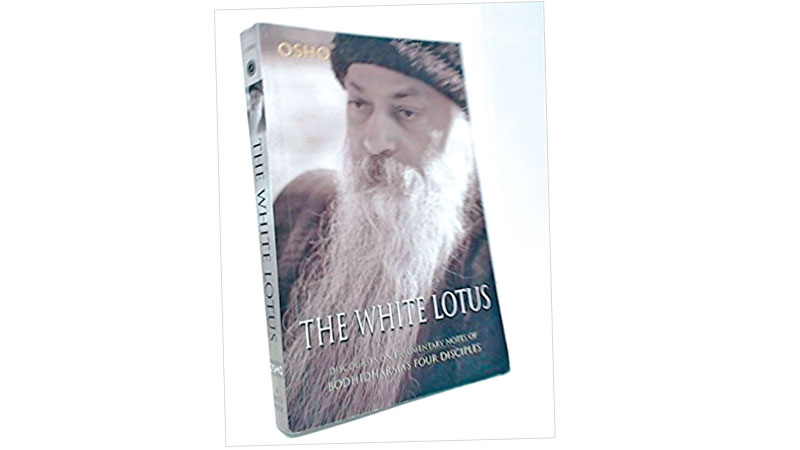

Though I am not familiar with the popular vision of Osho, I had the chance of reading one collection of conversations and dialogues on the Zen Master Bodhidharma, as compiled by Osho broadly titled as ‘The White Lotus’ (2014). This compilation of talks as delivered by Osho, the spiritualist is a compendium of visions, dialogues, interpretations, fables, poetic expressions, and above all insights based on Zen as laid down by its founder Bodhidharma. As such, the visions laid down centre around new spiritual findings as reinterpreted and age-old writings more known in China and Japan.

Though I am not familiar with the popular vision of Osho, I had the chance of reading one collection of conversations and dialogues on the Zen Master Bodhidharma, as compiled by Osho broadly titled as ‘The White Lotus’ (2014). This compilation of talks as delivered by Osho, the spiritualist is a compendium of visions, dialogues, interpretations, fables, poetic expressions, and above all insights based on Zen as laid down by its founder Bodhidharma. As such, the visions laid down centre around new spiritual findings as reinterpreted and age-old writings more known in China and Japan.

Nothing to realise

What Osho does is to present them in a new outlook to the modern reader. Spanning to eleven chapters, the compilers have taken care to present each chapter to a single point, though allowing the chance for diverse variations. The Chapter One titled as ‘Lotus Rain’ paves the way to know who a Tathagatha is. The answer is that he is one who knows that he comes from nowhere and goes nowhere. Then what is the Buddha? He is one who realises the truth and holds nothing that is not to be realised. Then what is Dharma? It is the norm of the universe.

The encounter of the two great personalities, Bodhidharma and Emperor Wu of China, is described as the starting point of the Zen doctrine. The situation is pictured dramatically allowing the age-old legends and the reality interlinked. Followed by the episode, several questions are being answered. What the Buddha mind is one such seminal questions Bodhidharma answers as your mind is it.

The questions and answers lead to stories both actual and fictitious, realistic and fantasy. When one chapter comes to a close, the reader comes across the utterance ‘Enough for today’ hinting that the question and answers are never ending.

Chapter Two titled as ‘Because I love you’ centres for the most part to forms of meditation. Osho underlines the process of meditation into a transformation of one’s self and one whole entity.

Rigid rules

The entire process of meditation is dealt in terms of events and incidents in the life of Osho. In one of the explanations as regards meditation, Osho says that strict rules can never make a good meditator, and says that no rules can help if imposed from outside. Instead, the process of meditation is a necessity, which is needed to make the mind conditioned by one’s own rules laid down by himself.

The concepts and interpretations pertaining to the belief in God and linked matters too are discussed at length. Why people believe in a god is tackled in many ways, paving way for one to reach one’s own conclusions. At one moment, he states: “If you really know what prayer is, prayer itself is its own reward. There is nobody else to reward you.”

Adds he: “If you enjoy dance, you don’t ask whether there is a god or not. If you enjoy dance, you simply dance, whether anybody is seeing the dance from the sky or not, is not your concern. Whether the stars and the sun and the moon are going to reward you for your dance, you don’t care. The dance is enough of a reward in itself.”

Perhaps Osho utilised Zen, instant enlightenment as a means to an end.

Textual content

The explanations and doctrinal interpretations seem to the reader as an attractive manner that grips the flow of reading the textual content of the book. The chapters are interlinked and for the most part, one sees the overlappings, which I feel is inevitable. There are dialogues that ensue between psycho analysts and patients. This paves the way for better awareness of the mind.

Can’t psychoanalysis help people know themselves on the broad issue? This is responded in many ways enabling the reader to gauge his own standpoint. Perhaps as Osho concludes a Buddha is normal, a Jesus is normal, a Zarathustra is normal, a Bodhidharma is normal. (But) you are not normal. You are simply average!

But as he further analyses psychoanalysis, simply helps you adjust yourself to the society you live in. It makes your life a little easier. Chapter Three which centres around the concept of Dharma attempts to interpret it not as a dogma, but as a process that reaches the life structure as a natural phenomenon. Several stories are laid down to interpret it explains the nature of Dharma, Osho explains what he means by Dharma as follows.

His explanation is cited as a response to a question raised by a disciple of Bodhidharma.

“By Dharma, remember: ordinarily it is translated as religion. That too is not right. Dharma is not religion. Religion is an attitude towards reality. Dharma is not an attitude towards reality. Dharma is simply living naturally, spontaneously. To live in, tune with nature is Dharma. A Zen master is reported to have said when asked what is Dharma, ‘when I feel hungry, I eat and when I feel sleepy, I sleep.’

Stress and strain

This book, which runs to eleven segments, differing from the common categorization into chapters, each contains varying types of approach to the broad aspects of living conditions aiming at alternative ways of thinking, resulting in a new way of living in a more relaxed manner, shredding off stress and strain. Perhaps a reader of ‘The White Lotus’ has the chance to transform.

The subtext or the inner layer of each chapter is intended to make the reader feel that he or she is freed from bitter material bonds in order to create conditions for the birth of a new kind of human being.

For the first time, I enjoyed reading ‘The White Lotus’ and recommend it to many others.

Add new comment