Most poetry teachers around the world teach their students to ask just one question. What is the intention of the poet in his or her poetic creation? The response may vary from culture to culture. But there may seem a unity in diversity. An English poem titled ‘Winter’ written in a cold climate in translation may look somewhat strange to a student living in a warm climate.

Most poetry teachers around the world teach their students to ask just one question. What is the intention of the poet in his or her poetic creation? The response may vary from culture to culture. But there may seem a unity in diversity. An English poem titled ‘Winter’ written in a cold climate in translation may look somewhat strange to a student living in a warm climate.

But the intention of the poet may be an elevated theme from the mere words. Similarly a poem written about ‘rain’ by one poet may differ both in the intention and in the meaning in two different ways. A poet may select a common experience of human significance and observation. But he may elevate the commonplace observation to a profound vision. Perhaps it may be a vision in metaphysics or realism.

Poetic structure

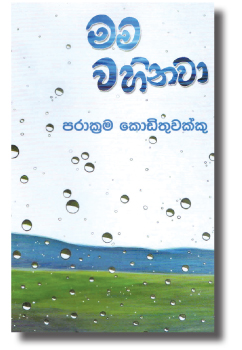

I felt the experience in several poems written by the Sinhala poet well known for his diversity in creations, Parakrama Kodituwakku. The poems I read are from his latest collection titled as ‘Mama Vahinava’ (I’m Raining). The poems that I preferred possess two layers or presumably more layers of meaning that go beyond the superficial outer layer of the poetic structure.

One good example is the title poem itself. The rain that pours down from the sky is created as a screen that separates four situations as visualised by the poet. The rain, while pours down, seems to declare:

“You had better

Discard the tattered clothes

Just fearlessly move

About on the rugged floor.

I am raining.”

The poetic metaphor is extended in several diverse ways.

“Can’t you bear up the

Burning anger

Within your mind

Will it burst out

Wait, I am raining.”

Followed by those lines, there comes the change in the metaphor.

“Perhaps there may have been a change of mind.

If you get detoured on your way.

Come back.

I’m raining.”

While the rain pours down like a screen, the poet sums up the inner feelings one ought to possess in the following lines.

“There is no compassion

Nor a kind mind

Leave the so called

Sanctified abode without fear

[for] I am raining”

Modern creations

For a moment I felt a certain degree of illuminated bliss. Perhaps what is lost in translation is poetry. The great poet Robert Graves was quite correct when he passed that verdict.

For me, it looks as if the senior seasoned Sinhala poet, Parakrama Kodituwakku, provides ample chances for the interpretation of the modern poetic creations, the diverse imaginative ways that could be utilised in the creative process. He transcends from the mere observation of nature to a profound layer. One example is the poem titled ‘Maha Bandana’ (The Great Bond). Here he takes a tree as bonded to the earth firmly (reminiscent of the Great Rooted Blossomer by Yeats).

It looks as if the great tree has spread his legs and hands to sky and rooted down with the head to the ground. What does the poet try to signify? The great firmness of the great continuity of existence of a bond is perceived by a tree and the earth. But he visualised the breakdown of that firmness at a particular moment. This could well be believed as the break of a great tree that symbolises the breakdown of the intimacy between nature and the earth if taken as a ‘great bond’.

The poem is characteristic of a metaphysical vision that emerges from a spiritual vision. Could one say that these are mere mystical entities? I dare not come to that conclusion. Most poetic visions lay in spiritualism and higher forms of mysticism. The feelings and visuals that we cannot perceive via sensory means cannot be distanced as mystical.

Creative barriers

As a result of the globalisation of human visions, the influence is felt in several instances. For example, the poet distances his creative barriers from his own cultural milieu and enters the world of other poets and poetesses such as Emily Dickinson. He attempts to recreate in his own terms some of the widely known epithets from other cultures. He treis to redefine in newer terms who a wife is. What it means by boozing, what is a message, what Goutama said, what are books, the way of the pseudo meditations etc.

In many ways, Kodituwakku depicts his own free will in poetic creations. He feels free to address certain characters he had read in narratives. For example, he addressed such a character in the poem ‘Isata Amatumak’ The comments he passes transcend the mere literary modes.

He uses the poetic compositions at times to dispel the adversities of intellectual dishonesty and denounces the same perhaps in a prosaic form. Thus some of the versifications are admixed into one entity of prose and verse which he terms as ‘gadya kavya’ or prose poems. He too reinterprets some of the rarely known folklore into a newly carved poetic form. One good example is the first poem titled as ‘Gonun Hathdenava Iskole’. The rediscovery of the place where a school is situated makes the poet recreate the age-old tale in a poetic room.

In a symbolic sense, the opem is a rediscovery of the man and the wildlife. The poem titled ‘Kirage Putaya, Kirige Putaya’ is yet a similar creation of the rediscovery and transformation of an age-old poem in a new manner.

A number of poetic creations centre round the experiences in the teaching profession linked to the remote schools in the country.

All in all, I felt that the poetic forms and contents are made to be fused in order to express the poetic feelings on the various complex conditions of human existence.

I feel that judgement cannot be given on the aesthetic value of poetry. They could be felt perhaps through an inner eye, from which we can see no great things, but even trivialities with great love.

Add new comment