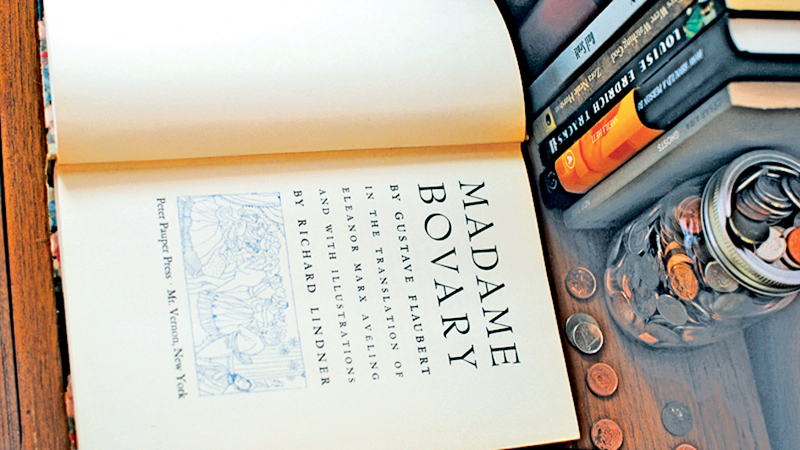

Not long ago, I was chatting with an older friend who is a retired engineer and also something of a writer, but not of fiction. When he heard that I had just finished a translation of Madame Bovary, he said something like, “But Madame Bovary has already been translated. Why does there need to be another translation?” or “But Madame Bovary has been available in English for a long time, hasn’t it? Why would you want to translate it again?” Often, the idea that there can be a wide range of translations of one text doesn’t occur to people—or that a translation could be bad, very bad, and unfaithful to the original. Instead, a translation is a translation—you write the book again in English, on the basis of the French, a fairly standard procedure, and there it is, it’s been done and doesn’t have to be done again.

A new book that is causing excitement internationally will be quickly translated into many languages, like the Jonathan Littell book that won the Prix Goncourt five years ago. It was soon translated into English, and if it isn’t destined to endure as a piece of literature, it will probably never be translated into English again.

But in the case of a book that appeared more than one hundred and fifty years ago, like Madame Bovary, and that is an important landmark in the history of the novel, there is room for plenty of different English versions. For one thing, the first editions of the original text may have been faulty, and over the years one or more corrected editions have been published, so that the earliest English translations no longer match the most accurate original. (2) The earliest translators (as was the case with the Muirs rendering Kafka) may have felt they needed to inflict subtle or not so subtle alterations on the style and even the content of the original so as to make it more acceptable to the Anglophone audience; with the passing of time, we come to deem this something of a betrayal and ask for a more faithful version. (3) Earlier versions may simply not be as good in other respects as they could be—let another translator have a try.

Each version will be quite distinct from all the others. How many ways, for instance, has even a single phrase (“bouffées d’affadissement”) from Madame Bovary been translated:

gusts of revulsion

a kind of rancid staleness

stale gusts of dreariness

waves of nausea

fumes of nausea

flavorless, sickening gusts

stagnant dreariness

whiffs of sickliness

waves of nauseous disgust

Dante on translation

Nothing that is harmonized by the bond of the Muses can be changed from its own to another language without having all its sweetness destroyed.

Every generation needs a new translation

Wise people like to say, Every generation needs a new translation. It sounds good, but I believe it isn’t necessarily so: If a translation is as fine as it can be, it may match the original in timelessness, too—it may deserve to endure. In fact, it may endure even if it is not all it should be in style and faithfulness.

The C. K. Scott Moncrieff translation of most of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (which he called, to Proust’s distress, Remembrance of Things Past) was written in an Edwardian English more dated than Proust’s own prose, and it departed consistently from the French original. Yet it had such conviction, on its own terms, and was so well written, if you liked a certain florid style, that it prevailed without competition for eighty years. (There was also, of course, the problem of finding a single individual to do a new translation of a three-thousand-page book—an individual who wouldn’t die before finishing it, as Scott Moncrieff had.)

Even though a superlative translation can achieve timelessness, that doesn’t mean other translators shouldn’t attempt other versions. The more the better, in the end.

Another pessimist: Auden on translation

When, as in pure lyric, a poet “sings” rather than “speaks,” he is rarely, if ever, translatable.

A swarm of flies

For a while I thought there were fourteen previous translations of Madame Bovary. Then I discovered more and thought there were eighteen. Then another was published a few months before I finished mine. Now I’ve heard that yet another will be coming out soon, so there will be at least twenty, maybe more that I don’t know about.

It happened several times while I was doing the translation that I would open a newly discovered previous translation of Madame Bovary and my heart would sink. I would say to myself, Well, this is quite good! The work I’m doing may be pointless, after all! Then I would look more closely and compare it to the original, and it would begin to seem less good. I would get to know it really well, and then it would seem quite inadequate.

For example, the following seems good enough, until I look at the original: “Ahead of them, a swarm of flies drifted along, humming in the warm air.” But they were flitting (voltigeait), not drifting—a very different motion—and they were buzzing (bourdonnant), as flies do, not humming. (“Warm air” is fine.)

Another example concerning insects occurs on the last page of the novel in a different translation: “Cantharides beetles droned busily round the flowering lilies.” Again, this seems fine until you check the French: “des cantharides bourdonnaient autour des lis en fleur.” Then you have to ask, why the gratuitous and rather clichéd addition of “busily,” which personifies the beetles—especially when Flaubert was at such pains to eliminate metaphor wherever possible?

If a translation doesn’t have obvious writing problems, it may seem quite all right at first glance, or even all the way through, if we don’t look at the original. We readers, after all, quickly adapt to the style of a translator, stop noticing it, and get caught up in the author’s story and vision of the world. And a great book is powerful enough to shine through a less than adequate translation. Unless we compare it to the original, we won’t know what we’re missing.

- Paris Review

Add new comment