Books on proper English do strangely well – perhaps because those who buy books are those who mind about apostrophes. Such volumes are supposed to improve your prose. But the true appeal seems to lie in a tasty kind of misanthropy: the reader gets to froth over dimwits who say things like, “She literally disappeared off the face of the earth”. But the language scold always loses in the end. Those kids who, thirty years ago, irked adults by saying “like” all the time are today saying “like” at board meetings, on national broadcasts, and to their own teenagers.

Whether ours is a time of butchered English or of flourishing invention isn’t obvious. Does online writing strip English of pomposity and outmoded rules? When Emmy J. Favilla turned up for her job interview at BuzzFeed five years ago, the media company already enjoyed notoriety as the leading trawler of click-bait, filling its webpages with enticing posts such as “Cat Enjoys Being Vacuumed”. The site had millions of views a day, and not a single copy editor. At first, BuzzFeed had been a mere side project for Jonah Peretti, one of the creators of the Huffington Post. His passion was to understand how ideas and information spread online, and this enterprise was his lab to track viral content. But he was onto something bigger than that. Financing poured in, humans were hired to oversee the algorithms, and he finally left the Huffington Post in 2011 to dedicate himself to the listicle capital of the world.

Original content

Peretti had discerned that social media were becoming a dominant reading source. He plotted the BuzzFeed expansion accordingly. “A big part of that is scoops and exclusives and original content,” he told the New York Times in 2012, “and it’s also about cute kittens in an entertaining cultural context.” Peretti employed a much-respected newshound, Ben Smith of Politico, as BuzzFeed Editor-in-Chief, and more appointments followed, including that of its first copy editor, Favilla. Almost at once, she had decisions to make, beginning with how you abbreviate “macaroni and cheese”.

Her ruling: “mac ’n’ cheese”, which she deemed cuter than “mac & cheese”. With that, she was off. In a mere two months, Favilla had drafted an entire style guide, thousands of words on preferred spellings and the like. When BuzzFeed posted a version online in 2014, old-school media sources treated the occasion as a milestone: the internet was growing up. Or, at least, someone could finally pronounce on whether you should say “de-friend” or “unfriend” (it’s the latter). All the attention surprised Favilla, and prompted her manifesto, A World Without “Whom”: The essential guide to language in the BuzzFeed age.

As if to immunize herself against criticism, she begins by announcing her paucity of qualifications; she is neither a lexicographer nor an expert in linguistics. Previously, she worked at Teen Vogue. “I am constantly looking up words for fear of using them incorrectly and everyone in my office and my life discovering that I am a fraud”, she says. But despite the tone of chirpy self-satire, what follows is a small revolution.

“Today everyone is a writer – a bad, unedited, unapologetic writer”, she says. “There’s no hiding our collective incompetence anymore.” Unlike the language scolds of yore, Favilla embraces the new ways, punctuating her writing with emoji, inserting screen-grabs of instant messages, using texting shortcuts such as “amirite?” Hers is a rule book with fewer rules than orders to ignore them. Humans are gushing out words at such a pace, they can’t be expected to bother with grammar, she says. More important is to be entertaining, on trend, popular (neatly matching the corporate goals of BuzzFeed). “It’s often more personal and more plain-languagey, and so it resonates immediately and more widely.”

Style ruling

Many of her judgements will chill traditionalists. She delights in the use of “literally” to mean its opposite. As her book title declares, she’d abolish “whom”, given how few people use it correctly. Other matters that have long rattled copy-editors don’t concern her: variations in spelling, comma precision, full stops in acronyms. Often, when pondering a style ruling, she offers no firm guidance, as if mistrusting authority to such a degree that she can’t grant it even to herself, the author of “the essential guide to language”.

“Use your judgment, friends”, she says. And: “Don’t sweat it too much”. And: “In the end, who cares?” Her chapter “Getting Things as Right as You Can: The stuff that kinda-sorta matters” features an instant-message exchange in which she corrects a BuzzFeed colleague on a style point. When questioned, Favilla lifts the rule, then admits to being drunk – “so whatever”. In this merry free-for-all, her scorn is reserved for those who scorn. A person who resists current usage is “stodgy and miserable and irrelevant”, prefers “a stagnant, miserable world”, and will be “sitting motionless in a puddle of his own tears”. She claims to want only to describe language, not prescribe its correct use. But her preference is clear, to raze what she deems pedantic and elevate the verbal etiquette of millennials. At times, she sounds like an activist: “We’ve come a long way, but we’ve still got some work left to do”.

Immersion in memes makes Favilla a handy guide for the perplexed – by which I mean people old enough to remember the twentieth century. However, she seems unsure where to pitch her book, leery of appearing uncool to her peers but needing to address those miserable geriatrics who somehow missed out on “cash me ousside, howbow dah”.

(This line was spoken by a thirteen-year-old girl on the daytime television talk show Dr. Phil as a threat to a derisive studio audience: “Catch me outside – how about that?” A clip of her saying those words became a viral hit, watched more than 100 million times on YouTube.

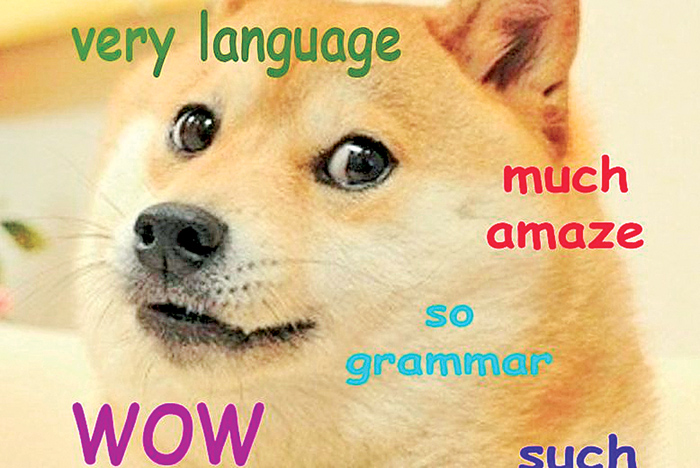

The girl, Danielle Bregoli, is now a celebrity.) Another meme Favilla explains for the web-blind is “Doge-speak”; a photo of a dog is superimposed onto other illustrations, then overlaid with phrases in broken English, as if to reflect the inane thoughts of the animal. In one, the dog appears at the Last Supper, thinking, “Such delicious” and “wow”.

BuzzFeed and its rivals dine on this sort of material, which is intended to be silly, often ironically. Fixing grammar in slapstick would be absurd, so Favilla’s practical rule for editing is this: “I ask myself, How would I write this in an email to a friend, or in a Facebook status?” What Favilla circles around is a striking proposal: eliminate formal English. If professional writing should read like an online message, and messaging is akin to conversation, there’s only one register. “Repeat after me”, she commands. “If we speak that way, it’s okay to write that way.”

- Times Literary Supplement

Add new comment