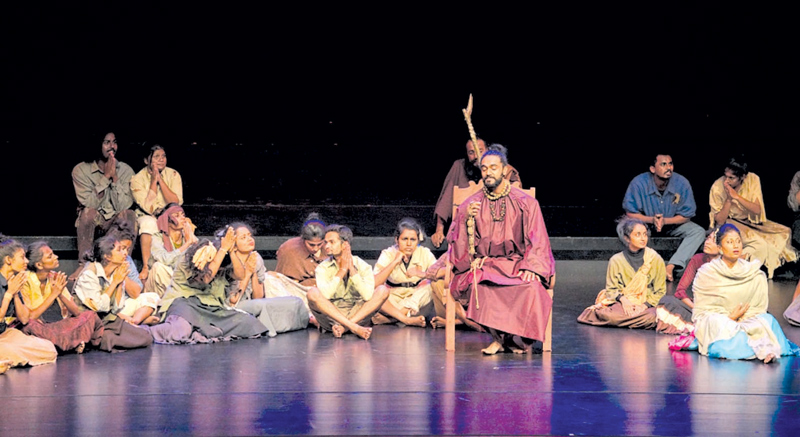

Then, with their extraordinary feat, the performers bathed the audience with a kind of a theatrical thrill. That concentration, simply unimaginable in a usual context of a theatre cast, made sure the audience is glued to their seats with no distraction at all.

At that very moment, you will realize that this play would not easily fit any other theatre apart from the Nelum Pokuna Mahinda Rajapaksa Theatre in Colombo.

When Nelum Pokuna was declared open to the public, it loomed large as a colossal waste of public funds. Sri Lanka’s theatre men beheld no use in the local edition of the amphitheatre. That was not without good reason. Nelum Pokuna was neither Lionel Wendt nor Lumbini. The artistes have to pay through the roof to gain good access, and unfortunately in Sri Lanka art does not mint big money on all occasions.

Then, by all means, there was one thespian who dared bite the bullet. He goes by the name of Ariyaratne Atugala widely known as the professor of mass communication at the University of Kelaniya. He entered the Colosseum to walk through and rushed in where his contemporaries feared to tread. He has now cracked a record by staging two massive productions at the Nelum Pokuna: Mahasamayama and Mahasupina. Note the prefix ‘Maha’ which denotes greatness or massiveness.

Colossal theatre

The common theatre is not really Atugala’s cup of tea. Mahasamayama was not open to the common man’s wallet – except on a few occasions when the production was ticketed at a nominal fee. Mahasupina, his second production staged at Nelum Pokuna, bears ample testimony to Professor Ariyaratne Atugala’s prowess in juxtaposing the ancient culture with the modernity.

What’s so special about Mahasupina?

It so depends on three lead figures: Tissa, Pariah and Sudda. These characters do not emerge as mere fillers or protagonists of a tale. They exemplify and illustrate unique concepts. Tissa stands for purity. But what of Pariah? Some of us are already familiar with the etymological links of Tamil which denotes foreign, hence unwelcome. In essence, Tissa represents the goodwill whereas Pariah stands for the evil forces. Pariah is the black crow and Tissa is the white swans that surround the black crow. But then they are both friends – at least at the outset. A third comer affects this friendship. And that is the third lead figure, Sudda, the one who makes a rift between the friends.

He listens to both friends and vests the Pariah with the sacred authority of jurisdiction. He does it on purpose. Those familiar with the Donoughmore and Soulbury constitution reforms and subsequent developments may well relate this to the ethnic conflict that the Whites created in Ceylon.

As the play progresses, we come to know that Tissa is, or represents, King Devanampiyatissa or his generation. The biggest challenge to the Devanampiyatissa generation comes from the Pariah generation that has birthed a lumpen society. Now this word, lumpen, is interesting as it is marked by a red-underline on Microsoft Word. The term is a shortened form of Lumpenproletariat, a term used primarily by Marxist theorists to describe the underclass devoid of class consciousness. Coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 1840s, they used it to refer to the "unthinking" lower strata of society exploited by reactionary and counter-revolutionary forces, in the context of the 1848 revolutions. Our dear old colonial masters or simply the Whites left a lumpen society as a challenge to the existing Devanampiyatissa culture already fading away in the country. This lumpen society earned a sobriquet: Kalu Sudda.

Timely choice

We have heard enough criticism of the kalu sudda behaviour in the country. However, Professor Ariyaratne Atugala walks a few steps ahead to place his criticism. He fishes out a piece from classical literature to sharpen his criticism of the lumpen society.

The piece is Maha Supina Jataka, which inspires the title and the contents of the play.

It seems a timely choice on several grounds. Maha Supina Jataka belongs to classical literature which is quite revered among the laity and the monks alike. The Jataka tale brings out 16 dreams – or nightmares – seen by King Kosol of yore. Whether he has enacted all the 16 dreams is not much important. Such exercises are best confined to schoolmasters who may need to offer a creative lesson of the Jataka tale. But Atugala’s objective is not to improvise all the dreams on the stage. As an academic of a fast-growing subject like mass communication, he wants to offer his interpretation of the lumpen society, its conflict with the accepted social norms and values and how that came to pass.

This understanding of the Jataka story introduces us to Tissa and Pariah.

To portray the Devanampiyatissa generation, Atugala makes use of video mapping. In the video screen appears the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta text inscribed on the ola leaves. This is noteworthy not really because Dhamamacakkappavattana Sutta has any reference to King Devanampiyatissa’s reign. Yet, the Sutta typifies the beginning of a long-lasting tradition. Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta influences important elements in the five discourses presented by Venerable Mahinda Thera. That the Venerable Thera ushered in the tradition of this country is common knowledge.

Tissa, Pariah and Sudda take us in a poetic adventure of classics, history and anthropology. Tissa belongs to classics. Pariah comes from history. Sudda inspires us to study humans. Atugala switches among classics, history and anthropology with much ease. Mahasupina Jataka belongs to classical literature. We need not worry about its authenticity.

Within high walls

What it tries to convey holds more weight than the worry of its authenticity. The Whites belong to history. What they have done is chronicled down in the text. What is most important comes next. Pariah belongs to anthropology where Atugala studies humans and human behaviour and societies in the past and present in between the Whites and the pre-White period.

These three characters supported by a coterie of characters move us through the abstract absurdity. It is the occasional silence that Atugala purposely instils that abstracts us. The walls are high with hardly any roof visible on the stage. The emotions ricochet explosively from the characters and smash into our spiritual flesh. Such an escape is necessary for the traditional entertainment enthusiast. When all the characters plod under the weight, we in the audience feel their burden.

Witnessing how Mahasupina unfolds in the giant Nelum Pokuna premises is an experience similar to watching Kung Fu in Red Theatre, Beijing. But there is a difference. In Beijing, the Kung Fu is shown on a daily basis. In Colombo, such an experience is merely a luxury.

With Mahasupina, Professor Ariyaratne Atugala has opened gates for new departures. Unfortunately, that is only a starting point with neither middle nor end in sight.

Add new comment