“One doesn’t give up being concerned for mankind because one acknowledges their fundamental absurdities and weaknesses. I still have hope that the human race can continue to progress.” (Interview with Gene D. Philips)

Some of the most visually intriguing movies I’ve seen from the last half-century were those directed by Stanley Kubrick. These have confounded me, a passionate cinephile, more than those of any other director. But then this is to engage in needless clichés.

It would be more appropriate to acknowledge their real contribution: like the thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock and the epics of David Lean, two other visual directors who count as his contemporaries, Kubrick’s work continues to exert a profound, inescapable influence on moviemakers and movie critics. The latter weren’t always kind to him – and some of them who weren’t kind remained unkind in their judgments of him long after his reputation in the industry had soared as high as it could – but then as he once rightly observed, “No reviewer has ever illuminated any aspect of my work for me.”

Movie directors who owe more than a tokenistic debt to him have been kinder and fairer. If their adulation of him hasn’t nudged down even after all these decades, it’s because the full weight of his influence on their work hasn’t nudged down either.

Perhaps the most recent example for that would be Yorgos Lanthimos, in particular The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). Visually stunning if not morbid, it owes its conception of its story – as macabre unbelievable as any story that plays around the supernatural against a secular, suburban landscape can be – to some of Kubrick’s works. Even Mike Flanagan, in Doctor Sleep (2019), made his sequel to The Shining (1980) more than a sequel: he partly incorporated Kubrick’s vision from the latter work. The results can be mixed – as in Deer, where the ending to me looked like a travesty to the achievements of the rest of the plot – but the influence, and the inspired direction, can’t be denied.

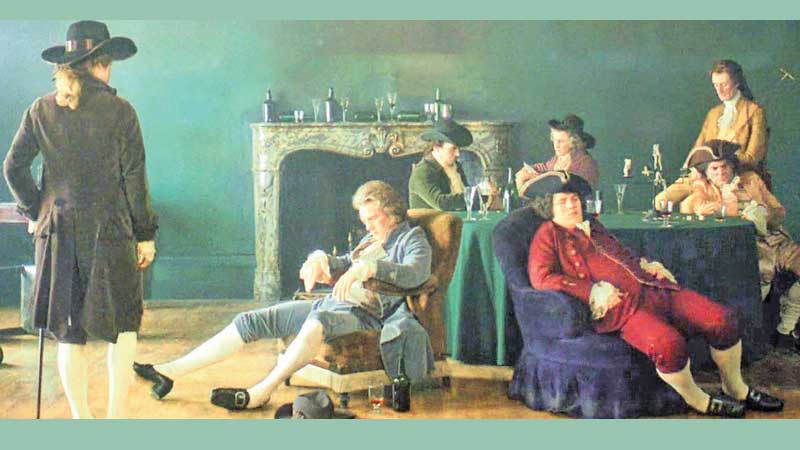

Napoleonic Europe

In a career spanning 50 years, Kubrick made just 13 films; roughly the number of films that Robert Bresson made over the same period. But Bresson operated in France at a time when Charles de Gaulle’s government had embarked on a lavish program to subsidise thriving artists. Kubrick received no such endorsement from any government – while making his second film at the age of 37, for instance, he had to collect $30 a week in unemployment compensation – and in fact, right before the peak of his career, he had to leave his country and settle in another. Thoroughly American, he remained an American to the last, and it’s a tribute to this that of the 13 movies he directed, only two – one set in Napoleonic Europe, the other in a dystopian future – were based in his new home, England.

Those 13 movies peddled so many genres that it’s hard to categorise him or to pin him to a wall. That’s where comparisons with Hitchcock and Lean fade away, though they remained as visual a couple of storytellers as he did. Hitchcock, in thriller after thriller, experimented in the same themes and motifs – an innocent man on the run, a witness to a crime which no one sees or believes happened, and a random Johnny on the street falling into a conspiracy – as did Lean in his epics. Kubrick, whose only experience in the epic left him disillusioned and encouraged him to leave home, did engage in thrillers, but only as far as they allowed him to straddle other genres: science fiction, antiwar, suburban drama.

Yorgos Lanthimos spares no one in The Killing of a Sacred Deer, not even the protagonist’s wife (played by Nicole Kidman, who incidentally was the main actress in Kubrick’s last film). His vision of humanity, if you can call it that, is at best cynical and at worst annihilating. He doesn’t let anyone off the hook, and as the story unfolds and we realise the true nature of the relationship between the doctor (Colin Farrell) and the boy (Barry Keoghan), we feel our pity for both evaporate. People aren’t good or evil, the director seems to be telling us; they’re good AND evil, and for the most, evil.

antagonist-protagonist unyielding

Lanthimos here is closer to Kubrick’s outlook on humanity than Flanagan was in Doctor Sleep. There’s hardly anything of the cynicism and the barbarity of The Shining in the latter. Stephen King, who famously hated Kubrick’s version of the original novel so much that he disavowed it and went on to make arguably the worst ever TV adaptation of a novel by the novelist ever made, loved Flanagan’s version of its sequel. He would have been responding favourably, perhaps, to the optimism and hopefulness in that sequel. Flanagan is by default a mainstream director, and nothing in the ending in Doctor Sleep suggest otherwise. Under Kubrick, however, The Shining gradually turns out to be merciless, cruel, and in its depiction of the antagonist-protagonist (Jack Nicholson), unyielding.

On at least one occasion Kubrick told an interviewer that, for all their absurdities and weaknesses, he sincerely believed “the human race can continue to progress.” The Shining, made at the peak of his career (i.e. when studios couldn’t refuse him even if what he made cost them a fortune), debunks this faint optimism. For that reason alone, the novel seems to be closer to Doctor Sleep’s hopefulness than its adaptation, and perhaps this explains King’s contrasting attitudes to Kubrick’s and Flanagan’s versions. Either way, it’s clear what Kubrick didn’t believe in: he didn’t buy all that crap about man’s innate goodness.

Like Satyajit Ray, Kubrick obsessed over every aspect of his productions, from the script to the music to the editing.

More than once he got into a conflict with his cast and crew; here one remembers Ray’s arguments with his cinematographer, Subatra Mitta, his editor, Dulal Datta, and his composer, the great Ravi Shankar (who he himself replaced after a while). The one time Kubrick allowed anyone to get above him was in Spartacus (1960), the most expensive production until then in cinema history, one seen today more as an actor’s (Kirk Douglas, who played the hero) and scriptwriter’s (Dalton Trumbo, who with it returned to Hollywood after being blacklisted for over a decade) than a director’s venture.

He could do this because, like Ray, he remained deeply versatile. He was always reading, always jotting down notes for his next film, and always engaged in research. When he met him for the first time in 1965, Anthony Frewin, the man who later wound up as Kubrick’s personal assistant (and much later, the representative of his estate), saw books upon books piled up: “There were hundreds of them – volumes on surrealism, dadaism, futuristic and fantastic art – in English, German, Italian, and other languages. There were works on astronomy, rocketry, cosmology, extraterrestrial life, and unidentified flying objects.” And it wasn’t just books: with his sharp eye and sharp ear, he was, until the very last, an avid photographer and an ardent lover of music. All these went into his movies.

Born in the Bronx to a suburban middle class New York family in 1928, Stanley Kubrick was the first of two children. His father, a physician and an amateur photographer, handed him a Graflex camera when he turned 13. At Taft High School, where he received the closest to a formal education, he became an official photographer of sorts. He was still studying there when, during World War II, he sold a picture to Look Magazine.

In 1946, after the War and after his graduation, he joined the publication, and at the age of 20 spent all his savings, a cool $3,900, on his debut short film, Day of the Fight (1950); “I had no idea what I was doing,” he later recalled. In any case, RKO saw it and brought it for $4000, giving him a profit of $100. It also advanced $1,500 for a second short, Flying Padre (1951). Two years later he directed his first feature work, Fear and Desire.

brief interregnums

The films he made thereafter have attracted critical attention like no other director’s films have. This is not a generalisation or a simplification, it’s a fact: browse through the archives, and see how many reviews, academic essays, entire books and tomes, have been penned on them. They all came one after another, after brief interregnums: The Killing (1956), Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975, my favourite), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999, which paired Tom Cruise with Nicole Kidman). Bleak yet momentarily hopeful, they reveal not just the flaws, but also the primitive state of nature within human beings: quoting Thomas Hobbes, they remain “nasty, brutish, and short.”

The reference to Hobbes isn’t arbitrary, much less is it random: more than one scholar has reduced Kubrick’s fascination with man’s penchant for evil – with no hope for redemption, as we see from the plights of the “heroes” in Lolita, A Clockwork Orange, and Barry Lyndon – to a fundamentally cynical and Hobbesian outlook on the world.This is in stark contrast to, say, the philosophy of Rousseau or Locke, which essentially says that human beings are good, and that it is the institutions set up to govern them which corrupt. Not really, Kubrick counters in his narratives: men are bad, and institutions just make them worse. If you don’t get a hint of that in The Sacred Killing of a Deer, you haven’t got the film.

And if you don’t get that in Kubrick’s works, you haven’t got him either. In that sense he remains the most enigmatic director, in the history of movies.