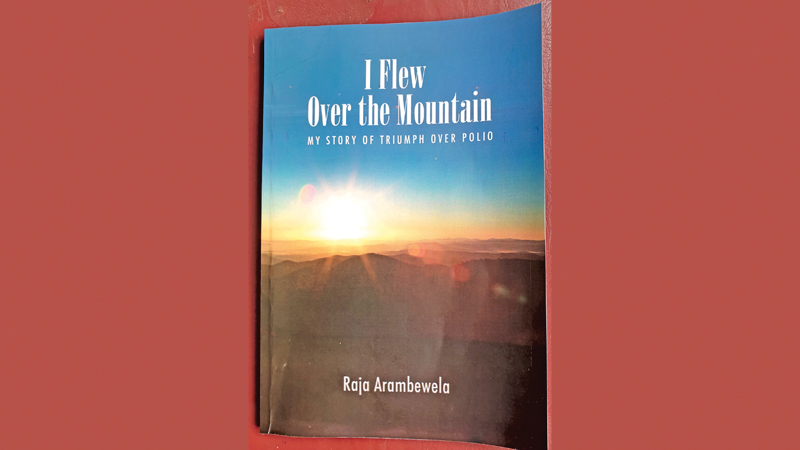

Title: I Flew Over the Mountain: My Story of Triumph over Polio

Author: Raja Arambewela

“Most of the time, I remained looking at the rickety ceiling above me making its creaking noise going round and round. I tried to interpret the sounds into words. Other times I repeatedly counted the number of wooden planks on either side of the fan as far as I could see”

The above excerpt from Raja Arambewela’s biography, perhaps, aptly represents how a debilitating physical condition, like polio, could act upon one’s vision and eventually one’s life. The vision that once offered vertical scrutiny has suddenly become horizontal, forcing the victim to convert trivial clatters to eloquent phrases and timber to an exercise in mathematics. This phrase also acts as a masquerade to a possible human response to a physical (and existential) crisis: the need to adopt, the need to transform a crisis into a catharsis—or in no-holds-barred words of Arambewela’s late father, falling into a hall and making that hole comfortable.

I Flew Over the Mountain: My Story of Triumph over Polio by Raja Arambewela is, as the self-explanatory title suggests, an autobiographical account of his life with polio. The book is written in three parts: Part I is titled Memories of a Childhood; Part II, Role of an Innovator and Part III, Autumn of my Life. For a first-time author, Arambewela’s ife narrative is crisp, compact, fluid and most importantly, sincere. Articulation of the complexities of someone grappling with polio aside, this book is admirable for its explication—indirectly though—of human feelings and emotions.

Human existence

In Part I, Memories of a Childhood, Arambewela journeys into his early upbringing in Bope, a picturesque hamlet in Galle; he was the youngest in a family of eight children. Here is human existence minus time, noise and stress in a hamlet of the late mid-nineteen-forties, only punctuated by a nation that was waking up to its new destiny amidst independence. Yet, the socio-political events of the nation seemingly took time to reach Bope, possibly owing to its rural setting. But not Polio, which seemed to have traveled there swiftly, because one month before the Polio vaccine reached Ceylon in March 1962, the disease struck down the 16-year old budding cricketer and football player Arambewela. “Sometime into the night, I woke up with a pain behind my knees…” was how the author remembers the very first brush with Polio.

The next morning was punctuated by a stiff neck and fever—all were considered normal events by his family who depended on intense affection and time-tested home-made remedies as a cure. He lost control of his legs the next day. “When I started walking my legs felt wobbly and I flung myself to the door a few steps away and held onto it prevent myself from falling…” he recalls. Thus, goes the author’s memory of his deep-seated feelings and emotions associated with an illness that actually threatened to destabilize, if not disrupt, his life. Arambewela also narrates how he came to terms with this new condition, how he absorbed the negative impacts of the condition to his life, and most importantly, his arduous journey towards, what Pink Floyd would sing as, ‘coming back to life.’

His narratives about finding love, finding employment, climbing the sacred Sripada mountain and escaping an LTTE bomb all combine to add suspense to a narrative whose main thematic focus is physical disability.

Narrative spirit

For an autobiography that began in melancholy, Part II of the book offersrecompense. Titled Role of an Innovator,here we find a much more spirited author, retired from his employment, yet searching for ways and means to project his youthful heart beyond the confines of the boundary walls at home. More than a narrative about innovation, this is a travel memoire. The author takes a reader on a journey into his new life in the nature tourism sector.

Here Arambewela negotiates jungle terrains to set up luxury camping sites for tourists, takes hikes along difficult trails (while hiking along the Kalthota river he and his party scares away illegal gem miners), at one point in the hike along the Kalthota river he and his companions brave a mountainous path adjoining a precipice, which was “one foot wide at its widest point and about eight to nine inches at other places…forty feet long”; he also searches for the traces of the legendary king Ravana in Maha Eliya Thenna and in the unreachable caves called Sthripura where Sita was supposedly hidden away from the lustful male gaze. One could say Arambewela of the first part of the book is unrecognized here, for the narrative voice in this section is that of a spirited and hungry seeker of the natural world.

Part III (Autumn of my Life) is unpredictably short and narrates the inevitably of old age and casts a reflecting stance back to a life which negotiated an impossible physical condition. “After polio I fought back and won. This was a return bout. I was in the ring again, fighting back and I wanted to win”thus narrates the author, of course in reference to Anno Domini than the illness. No one wishes to grow old and not one wishes to pause, so we readers forgive the author for his brevity of narrative.

Maiden attempt

Arambewela’s maiden attempt at writing for all its good intentions, lapses when it comes to explicating details. His early life and the immediate aftermath of him contacting Polio, might be the point of interest for many a reader of this book—for Arambewela is an insider, a subject of Polio, and one would want to comprehensive details of his condition. Some of his potential younger readers would not have ever seen a Polio victim.

Thus, his narrative of his early life could do with, metaphorically, more ‘meat’ in terms of narrative and even photographic evidence. After all even in his sparse descriptions, his home town Bope glistens with natural charm, the scenic Richmond College Hill and the prefects’ point of duty near Rippon College all create images of color and delight. Thus, photographic evidence from an old photo album would have served the author’s purpose well. The same criticism applies to Part II of his book where he recounts his travels to exotic and concealed locations in Sri Lanka, and such situations demand rigorous descriptions and if possible, visuals. Such additions would have convinced a reader of the author’s sense of arduous physical achievements as a victim of Polio.

Yet, in defense of Arambewela, this book is a more than a sharing of his life experiences with an invisible readership. His labor of love is a proof to himself that he survived an impossible physical disability and lived to tell the tale. A narrative whose raison d’etre is self-conviction than anything else. Arambewela’s father, a gentle-giant of a human personality, might have been proud of his son, for Arambewela had actually followed his aphorism: If you get into a hole, make that hole comfortable. Arambewela might have not only made the hole comfortable, he also used the hole as a spring board to touch the peaks of height.

Reviewed by Lal Medawattegedara