Prof. Jayasuriya who was born on February 14, 1918, won a scholarship to the University College, Colombo, securing the third place at the Cambridge Senior Examination held in 1933. Due to his logical thinking skills, he graduated at the age of 21 with a First Class in Mathematics. Having to state the name of the Buddhist school he was serving at the selection interview, young Jayasuriya failed to attain his career ambition of joining the Civil Service. Jayasuriya, never repenting this, has stated later that had he joined the Civil Service, he would have lost his mission in life.

In 1947, Prof. Jayasuriya proceeded to the UK to follow Postgraduate Studies at the Institute of Education, London University. Back home in 1949 with a Postgraduate Diploma and a MA in Education, he was appointed tothe post of lecturer in Mathematics at the Teacher Training College, Maharagama. In 1952, he joined the Education Faculty of the Ceylon University and became the Professor of Education in the same university by 1957. He retired from university service in 1971 to accept an assignment in UNESCO, Bangkok, as the Regional Advisor in Population Education.

At the completion of this assignment, he returned home and engaged in research and publication and in a variety of projects in an advisory capacity, until his demise on January 23, 1990.

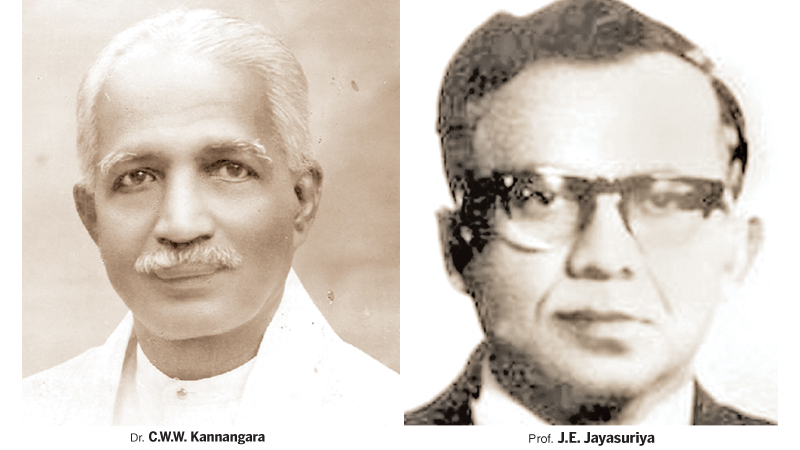

Prof. Jayasuriya had been an exemplary teacher, educational administrator, author, researcher, policymaker, international consultant as well as a devoted family man. He was considered a born teacher with all the characteristics of an exemplary model of an educator. His lessons, interspersed with questions, anecdotes, jokes and remarks had been very interesting to his students. Moreover, his ability to inculcate skills in the learner with practical examples rather than probing much into theory, shows how advanced he had been as a teacher. As a graduate of 21 years, he demonstrated success in managing a prestigious school in Colombo with experienced senior teachers. It is in recognition of his administrative capacity that the then Education Minister Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara handpicked him for the headship of the Central College that was established in the Minister’s electorate, Matugama. Moreover, serving the Education Faculty of the Peradeniya University for 15 years as the Professor, Jayasuriya made it one of the best Faculties of Education. The Bachelor of Education Programme he launched at the same university also demonstrated instant success.

Prof. Jayasuriya has written three sets of books on Arithmetic, Algebra and Geometry for schoolchildren from Grade 6 to GCE O/L. His idea to produce school texts sprang from the change in the medium of instruction from English to mother tongue that called for new textbooks in the national languages. The texts he produced were used widely by schools until the government introduced the free textbooks policy in the 1980s. Educational Policies and Progress during British Rule in Ceylon (1796-1948) and Education in Ceylon Before and after Independence (1939 to 1969) are two of his publications wherein he discusses policy matters related to free education and controversial issues related to the medium of instruction, teaching of religion, denominational and government schools and curricular diversification. He has also published over 150 research papers on different aspects of education.

Prof. Jayasuriya’s contribution to the field of policy formulation in education is also outstanding. His able guidance and leadership as the Chairman of the National Education Commission established in the 1960s, to propose policy for the period after the takeover of assisted schools, enabled the Commission to come up with some far-reaching proposals for a national system of education.

In recognition of his great contribution to the education of Sri Lanka, Prof. Jayasuriya was awarded the prestigious honour of being the first speaker of the C.W.W. Kannangara Memorial Lecture Series, inaugurated by the National Institute of Education (NIE) on October 13, 1988. On this occasion, he chose to pay his tribute to no other than the great Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara, the Father of Free Education in Sri Lanka, whom he held in high regard. His memorial lecture entitled “Democratization of Education: Contribution of Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara” is of special significance as it was delivered at the age of 70, just 15 months before his demise, at the height of a life enriched by knowledge and experience. On the 103rd birth anniversary of this great academic, the writer highlights what Prof. Jayasuriya appreciated and admired in Kannangara, in order to shed light on the very values and principles which he himself cherished and held dear to his heart.

Prof. Jayasuriya begins his lecture by acknowledging the privilege he had received to pay his tribute to one of the greatest Sri Lankan patriots. Highlighting the fact that Dr. Kannangara’s contribution to education far transcends that of his contemporaries, he justifies the selection of Dr. Kannangara as the first educator to be honoured in this manner. To provide more scope for assessing Dr. Kannangara’s contribution, he also introduces the term “democratization of education” that Kannangara has used in place of the common term “free education.”

Moving on to sources that he has used in preparing for the lecture, Prof. Jayasuriya mentions the late K.H.M. Sumathipala’s book on the History of Education in Ceylon, 1796–1965. Observing that a greater part of the book provides a well-documented account of Dr. Kannangara’s life and work, he boldly states that the title of the book is misleading. Prof. Jayasuriya refers to the two books he had written himself, and says that he used these books in preparing for the lecture. Acknowledging that he has drawn a few facts from the first source, he affirms that all the comments and interpretations he is using in the lecture are his own.

Prof. Jayasuriya begins his tribute to Kannangara by discussing his educational and career attainments.He starts from the church where he was baptized and moves on to his early education that enabled him to access a better quality education by winning a scholarship in open competition. In appreciation of the gratitude that Kannangara demonstrated to the principal of the school, who had recognised and nurtured his great potential, Prof. Jayasuriya states that Kannangara set aside his ambition to enter the Law College for a while to yield to the principal’s request to serve his alma mater. Prof. Jayasuriya goes on to explain how Kannangara gained recognition as an exceptional teacher of Mathematics due to the outstanding performance of his students in the subject and how he also excelled in his career as a lawyer when he fulfilled his career ambition later.

Prof. Jayasuriya also highlights the school day talents of Kannangara in the areas of General Proficiency, Mathematics and English and how he also excelled in Pali and Sinhala while getting the best of the British public school tradition. He mentions the commanding heights Kannanagara reached in both law and politics and the ‘felicitous phrase and paper thrust’ that were in his repertoire for use as occasion demanded. He also brings to light how Kannangara was beaten by a candidate in an all-island scholarship examination that selected just one student for studies in a British University, and how one journalist disregarding the fact that he was among the cream of the country’s youth in terms of intelligence and learning, ridiculed him as a small man who was denied a good education. Thus, Prof. Jayasuriya highlights the special talents of Kannangara, his successes and failures, the praise and ridicule that came his way along with some of his strong personal qualities such as his loyalty to his guru and his love for the national heritage.

Discussing Kannangara’s early promise, Prof. Jayasuriya declares that Kannangara was no stooge, no chauvinist nor turncoat. Without these personal qualities, Prof. Jayasuriya claims that Kannangara, would have floundered half way, preventing his magnificent contribution to the progress of education in Ceylon. To justify that Dr. Kannangara was no stooge, Prof. Jayasuriya brings to light how he chose to resign his appointment to defy a manager’s order to support his candidature at a Local Board election. To support the fact that Dr. Kannangara was no chauvinist, Prof. Jayasuriya refers to an incident which demonstrated that Kannangara was free of ethnic prejudice. He goes on to explain how Kannangara canvassed untiringly for a person of a different ethnic group who was engaged in a contest with a person from Kannangara’s own ethnic background. Furthermore, Prof. Jayasuriya reveals how this action enabled Kannangara to be selected repeatedly as the Chairman of the multiethnic Executive Committee of the State Council, an office associated with the ministerial portfolio for Education. To prove that Kannangara was no turncoat either, Prof. Jayasuriya mentions a financial situation where the government was compelled to introduce an ordinance to impose Income Tax. Considering income tax as an equitable form of taxation, he goes on to explain how Kannangara voted for this Ordinance in both the readings at the State Council, at a time when the majority of people’s representatives, yielding to the power of a European lobby, opted to change their stand.

Prof. Jayasuriya next turns his attention to the Executive Committee of the time which played a significant role in the democratization of education. He highlights that this Committee until 1939, had no powers to exercise its supposed functions and refers to this as “the struggle for power of a powerless Executive Committee, 1931-1939.” He then discusses how the egalitarian ideology of removing inequities and inequalities became the dominant motivation of the Committee thereafter. To this end, Prof. Jayasuriya notes the effort made by Kannangara to establish a new system that would ensure genuine democratization of education by providing equal opportunities to all children of the country, irrespective of their social class, economic condition, religion and ethnic origin. He identifies Kannangara as the man unwavering in this struggle, who strove with an iron will against overwhelming odds. Referring to other politicians who supported Kannangara, he says that several of them went only part of the way, a few most of the way, and just one nearly all the way.

Prof. Jayasuriya opens his discussion on the free education scheme that wasintroduced in 1944 by referring to the education context of 1943. He clarifies that it was the medium of instruction - English or bilingual – and not the type of school attended - government or assisted - thatbrought about the inequality of education. Knowing that the official language of the country was English and that ‘no one without the knowledge of English can fill any high post,’ he reports how the rich and the influential sent their children to fee levying English schools, leaving the gifted children of the poor to thelow paid jobs of vernacular teacher, ayurvedic physician or notary.

In order to make equality of education a reality, Prof. Jayasuriya brings to light the recommendations made by the Kannangara Committee not only to make education free in all schools but in institutions of tertiary education as well. He highlights how Dr. Kannangara considering free education at all levels as the panacea, fought for the acceptance of the scheme by stating, “we shall be able to say that we found education … the patrimony of the rich and left it the inheritance of the poor.”

In responding to a comment made by the Financial Secretary in relation to the high cost of free education, Prof. Jayasuriya brings outthe subtlety with which Kannangara dealt with the commentby claiming that the proposals are placed only to promote discussion with no commitment expected in respect of the extent or the date of implementation.He also highlights how Kannangara in his ministerial speech to the State Council meted out a devastating treatment to certain wealthy and prominent citizens who argued for the deferment of the proposals on the ground that their adoption even in principle would materially affect not only the system of education but also the entire economic and social organization of the island. Prof. Jayasuriya also brings to light the formation of the Central Free Education Defence Committee and the islandwide campaign it conducted to make sure that the Bill would not be shelved. Moreover, he indicates how the mass support for the Bill thus made two councillors withdraw their proposals for deferment and how the Bill was passed on May 27, 1947. Irrespective of the struggle, Prof. Jayasuriya observeshow the adoption of the principle of free education acted as a bonanza to the well-to-do by allowing them to receive free of charge the high-quality education for which they previously had to pay, while letting the masses continue with the poor quality education that had always been free for them.

In this context, Prof. Jayasuriya recognizes Kannangara’s effort to establish central schools as a step of far-reaching importance for the democratization of education in Sri Lanka. At a time when Royal College alone, among government schools, was providing a quality education to the children of well-to-do parents in Colombo allowing them to achieve higher education and lucrative employment, he highlights Kannangara’s aim to provide through central schools a similar type of education at least to a small number of the most gifted rural children of the country.

Prof. Jayasuriya identifies the staffing of central schools with the best teachers available as a revolutionary measure that facilitated this aim. He explains how this was initiated by creating a Grade II Special post for the headship of Matugama Central School and how this post was stepped up within months to a Grade I post.

He goes on to explain how this move enticed heads of assisted schools to join Central schools, making assisted schools to lose their best teachers to Central schools. Referring to the first distinction in Mathematics gained at the SSC in Matugama Central School, and declaring this as the first from a government school other than Royal College, Prof. Jayasuriya highlights how the recruitment of quality staff made Central schools, centres of excellence equaling Royal College. Furthermore, he highlights the success achieved by Matugama Central School in sending students to the universities first for Arts, and later for Science, and how other central schools followed suit soon after. All in all, he proudly declares how Central schools were thus able to rival long-established assisted schools, opening vistas of hope and opportunity to thousands of able students in rural Ceylon.

Prof. Jayasuriya also sheds light on Kannangara’s effort to give the national languages their rightful place in the education system. To this end, he describes the inferior status given to the national languages within the education system of the time although the vast majority of people were literate only in the national languages. He elaborates that it was only seven percent of the population that was literate in English by the early 1940s, irrespective of the fact that it was the English Language that held the position of pre-eminence in educational and administrative settings.

Prof. Jayasuriya goes on to explain how Kannangara placed a set of recommendations before the State Council in May 1944 to establish the sole use of the mother tongue as the medium of instruction at the primary level, the use of the mother tongue or the bilingual system as the medium of instruction at the post-primary lower level, and the mother tongue, the bilingual system or English as the medium of instruction at the post-primary higher level. He delightfully points out how this initiative enabled the introduction of Sinhala and Tamil as the media of instruction in post-primary classes, and how it enabled the action to be extended to the tertiary level with the admission of Swabhasha educated students to the universities.

Prof. Jayasuriya also discusses the attempt made by Kannangara to rationalize the school system. He begins his discussion by introducing the three types of schools - government, denominational, and others managed by private authorities - that were supported by state funds. Next, he explains how the introduction of free education and the accompanying liberal grants made available to denominational schools generated a need for school rationalization. These schools were given 75.2 percent of the government grant while the government treated its own schools with much less generosity. Prof. Jayasuriya explains how Kannangara put forward a proposal to the State Council to make school funding more equitable. He elaborates how Kannangara made his stand on denominational schools abundantly clear by acknowledging that ‘where duty demands that justice shall be done,’ the service rendered by these schools in the past ‘should not stand on the way of our taking proper action.’ However, in spite of the fact that rationalization of the school system was necessary for the true democratization of education, Prof. Jayasuriya admits that it did not take place to the disappointment of Kannangara.

Prof. Jayasuriya highlights the efforts taken by Kannangara to make religious education a part of the school curriculum in government schools. Explaining the situation that existed at the time, he says that both assisted and government schools were given the opportunity to impart religious instruction to students of their religious denominations, but government schools could do so only before or after the regular school sessions. Prof. Jayasuriya mentions that Kannangara took action to lift this ban so that government schools could impart religious education during school sessions just like the assisted schools.

Prof. Jayasuriya also brings to light Kannangara’s steadfast devotion to the ideal of robust and unexploited teaching profession in order to make democratization of education a success. He points out that Kannangara’s efforts to eliminate the private sector in education was also motivated by his determination to put an end to the unfair treatment of teachers within the sector.

In the last section of his lecture entitled “Kannangara’s contribution and martyrdom,” Professor Jayasuriya sums up how Kannangara, for 16 years, strove unceasingly to throw the doors of educational opportunity wide open to every child born to this country. With any cause likely to be beneficial to the common people of the country being dear to his heart, he says that Kannangara became theirardent champion, displaying at all times a dogged perseverance and fearless advocacy to defend their rights.

Prof. Jayasuriya pays his final tribute to Kannangara by harking back to a presidential address that he delivered in Calcutta during his last year of office, and quoting the following eloquent words of Kannangara that enshrine his justifiable pride and satisfaction at his own achievements as the Education Minister: “… in spite of abuse and calumny, vilification and ridicule, I have succeeded in obtaining the sanction of the State Council of Ceylon for a scheme of free education, providing for all children of the land equal opportunity to climb up to the highest rung of the university, … and for obtaining for our national languages their rightful place in that scheme as an essential prerequisite for building up a free, united and independent nation.”