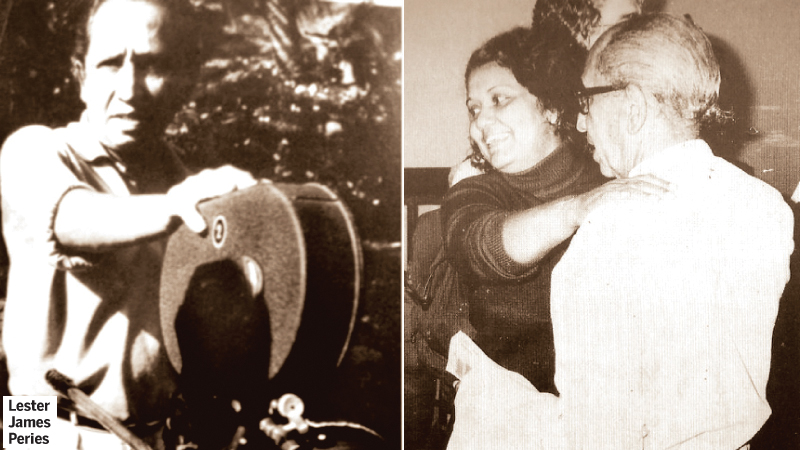

Had he been alive, Lester James Peries would have turned 102 on Monday. The definitive director of this country, he was also one of the few definitive directors of his time, sharing the latter distinction with a great many others: Satyajit Ray, Ingmar Bergman, Andrzej Wajda, Robert Bresson, Akira Kurosawa, and Jean Renoir.

Had he been alive, Lester James Peries would have turned 102 on Monday. The definitive director of this country, he was also one of the few definitive directors of his time, sharing the latter distinction with a great many others: Satyajit Ray, Ingmar Bergman, Andrzej Wajda, Robert Bresson, Akira Kurosawa, and Jean Renoir.

What did he have in common with these auteurs? A fascination with life, and a curiosity about individuals. The human character, the human condition – what Balzac called “La Comédie humaine” – is what adorns most of his films, and it is what makes up the films of those other directors. Ingmar Bergman once observed that the human face remained the most important subject of the cinema. That was Lester’s view also: there are moments in his stories where the protagonist has an epiphany, and the camera ponders his face.

If I were to think of an analogy from another art form for Lester’s best work – his middle-period between Gamperaliya and Nidhanaya, in particular his Ceylon Theatres trilogy – I would invariably think of the French impressionists. When Robert Bresson made his film of Joan of Arc, he criticised Carl Dreyer’s version for its excesses. The facial expressions, the gestures, the emotions: these seemed over the top, hardly restrained. Bresson was, in that sense, a master at subtlety, and the characters in his films reveal very little. I’m not by any means trying to compare Bresson with Lester, but in how both restrain their actors, and with them their performances, they were as fond of subtlety and nuance, of emotional depth, as the French Impressionists had been long before them.

Penultimate sequence

To pick a specific example from one of his films would of course be a challenge, but if I were to pick one, I’d invariably go for the penultimate sequence of Delovak Athara. Those who’ve seen Delovak Athara will remember what unfolds there: Nissanka (Tony Ranasinghe in his best performance), having fought with his conscience over whether or not to confess a crime he’s committed to the local police, battles with the guilt of knowing his manservant has been framed for that crime by the police and his overprotective parents. As Nissanka walks slowly and wearily near a lake, the camera follows him and frames him against a tree. He looks up at the rustling leaves in a rare moment of solitude (he’s never free in the film). The wind dies down, and he looks down. Amaradeva’s plaintive music builds up, and the camera zooms in on his face. As he lifts his face, the faintest teardrop trickles down his cheek.

To pick a specific example from one of his films would of course be a challenge, but if I were to pick one, I’d invariably go for the penultimate sequence of Delovak Athara. Those who’ve seen Delovak Athara will remember what unfolds there: Nissanka (Tony Ranasinghe in his best performance), having fought with his conscience over whether or not to confess a crime he’s committed to the local police, battles with the guilt of knowing his manservant has been framed for that crime by the police and his overprotective parents. As Nissanka walks slowly and wearily near a lake, the camera follows him and frames him against a tree. He looks up at the rustling leaves in a rare moment of solitude (he’s never free in the film). The wind dies down, and he looks down. Amaradeva’s plaintive music builds up, and the camera zooms in on his face. As he lifts his face, the faintest teardrop trickles down his cheek.

Philip Cooray in his book on Lester, The Lonely Artist, critiques this particular scene as being too intellectualised, too unemotional, too cold and distanced, an allegation he throws at the whole film. Yet I think Cooray adopted the wrong criterion in assessing the sequence, for there is a semblance of emotion and empathy that Lester compels from the audience. By this point in the narrative the protagonist has undergone a subtle if not profound transformation: from the amoral, indifferent bourgeois he was to a more sensitive, empathetic everyman. That transformation isn’t entirely his doing: it’s more so that of Chitra (Swineetha Weerasinghe), who encourages him to confess and be through with the crime.

More importantly for me, this particular sequence brings up Lester’s penchant for revealing what a character is feeling without betraying too much expressiveness. There is a moment in Jean Renoir’s La Règle du Jeu (1937) where Robert (Marcel Dalio), married to the woman at the centre of the story, ponders a mechanical contraption, a calliope, in the dark, as it plays to the audience. Remembering this scene years later, Dalio told an interviewer that they had to reshoot it – all 30 or so seconds of it – for two days.

Buried contrasts of feeling

What was so difficult for Dalio were the sentiments he had to project: between pride at showcasing his toy, and reticence at having to showcase it to such a large audience. The final take is breathtaking: Roger Ebert calls Robert’s face, and the buried contrasts of feeling on it, “a study in complexity.” Renoir said it was the best shot he ever filmed, and it shows: it justifies what Bergman would say of the human face decades later.

Seeing Delovak Athara after all these years, I can’t help but remember Robert’s face at the exact moment Nissanka, looking at the camera, lets a teardrop trickle down. Cooray was only half-right when he called it unemotional and intellectual. Delovak Athara may well be the least emotional film Lester made, but that is not to say he eschewed emotion altogether. In any case, I believe the point of scenes like this isn’t so much to deny emotion as it is to show how some of us condition ourselves to deny it.

Nidhanaya |

Like Robert from La Règle du Jeu, Nissanka’s face reveals the buried complexities, if not complications, of emotion (sadness and desperation in Nissanka’s case) woven into the very theme of the film. If the purpose of Robert’s face in Renoir’s film is to show that on the verge of war human beings still delight in their foibles and yet pretend not to show it, the purpose of Nissanka’s face in Lester’s movie is to show that the conflict between one’s desires and one’s conscience is never easily resolved. It hardly need be added that in conveying to the viewer the nuances of such contrasts and complexities of feeling, these works transcend the limits of their medium, and become almost painterly and impressionistic.

Delovak Athara remains my favourite film by Lester, for several reasons: first and foremost, for being the closest to a truly independent work he engaged with. The cinematography has never been better in his other works, except perhaps for his Ceylon Theatres trilogy; opting for shades of grey over chiaroscuro blacks and whites, it occupies a peculiar moral universe, teetering between the moral ambiguity of Nissanka, the over-protectiveness of his parents and his fiancée’s family, and the morally and ethically right stances of Chitra.

Flawed antiheroes

I remember Lester critiquing Satyajit Ray in an essay over what he felt to be the latter’s simplistic understanding of human beings: there are no villains in his films, only heroes and flawed antiheroes. Lester may have made this critique when his films had their fair share of antagonists (as with Baddegama), but seeing Delovak Athara today, I’m struck by how easily one can make the same allegation about his early work: that they lack a complete villain, and that every character, right down to the least likeable among them, can be understood and even sympathised with by viewers. To give one example, the mother and father in Delovak Athara do all they can to deflect attention from their son, yet even as they frame their manservant, we understand (though not empathise with) their motives: having just one child, and a son at that, they want him kept out of trouble at any price.

It’s rather unfortunate that he made his best work – the crest before the trough in his career – at precisely the time when the politicisation of Sri Lanka’s cinema was in full sway. Starting with the critics, then going over to the directors of the next generation, one by one they made the allegation, wholly unjustified when we read it now, that Lester’s conception of the cinema was removed from more mundane, but more relevant, political matters.

Insofar as their belief that Lester seemed incapable of making a political work is concerned, they were not wide of the mark. For all his humanism, Satyajit Ray directed three political films: the Calcutta Trilogy. The closest to a political statement, let alone a film, that Lester came up with, was the scene in Yuganthaya where Simon and Malin Kabilana – moneyed father and Marxist son – engage in a heated debate over the rights of the working class. And yet, in the framing of this sequence – the debate between father and son is never followed up, and seems to unfold in isolation from the rest of the story – one feels Lester focused attention on the personal conflict – between one generation and the next – rather than the more relevant capital/labour dialectic Martin Wickramasinghe explored in the novel.

But to conflate this general inability to make a political statement with a generic inability to make any socially conscious statement, political or otherwise, would be to put the cart before the horse. Humanism has been deemed too inadequate, even insensitive, by several Marxist scholars; with its origins in 19th century bourgeois European philosophy, they feel it does not do enough to reveal the relations of production, of social forces, which undergird society as it is and as people experience and live through it. The reason why Lester’s works do not meet this criterion is that they project a vision of humanity, a humanism, that doesn’t concern itself much with the issue of class. This critique is shared by several scholars, yet it is one that has been itself critiqued by other scholars, both Marxist and non-Marxist.

To what they’ve said I can add only this much: the idea that “socially conscious” films must of necessity resort to explicit political symbols – and many films that projected themselves as socially or politically conscious have resorted to such symbols – is to abandon the diversity if not complexity of an art form. Lester’s films are hardly the socially detached or politically irrelevant works of art they are made out to be by their critics. If this were the criterion to be employed in dissecting a work of art, Philip Gunawardena wouldn’t have considered Delovak Athara a favourite and Engels wouldn’t have said he preferred the reactionary Balzac to the more radical Émile Zola. Lester himself offered the best critique of these critics: that while he worked with human beings, they preferred to work with symbols.