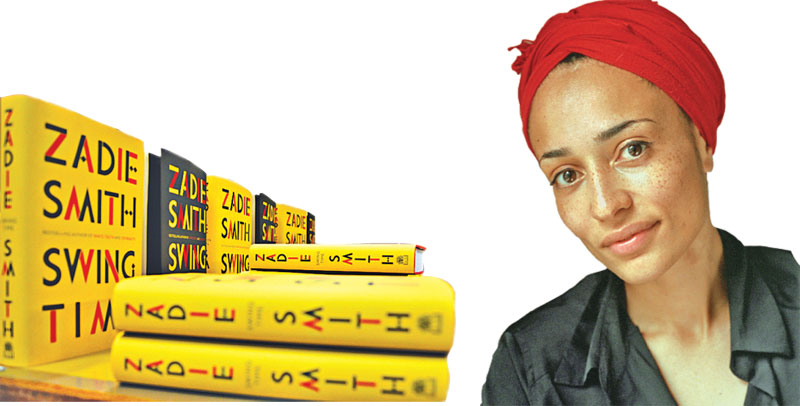

If my stars had been kinder, I would have met Zadie Smith at the Department of Creative Writing, New York University, in 2010. But our paths were never destined to meet. As fate would have it, by the time she joined the faculty as a lecturer I had bid adieu to my graduate studies at NYU and returned home. Among all the contemporary writers that thronged the classrooms, escalators, cafes and streets around NYU, I so yearned to bump into Zadie (in her turban, thick-rimmed glasses and big trainers) because I found her alluring, not only as a novelist, but as an essayist and an advocate of the minimum-makeup movement (“When I was growing up,' she once said, “just the whole idea of being a girl — it seemed like a lot of work to me. Even now, I will wear lipstick and mascara but I will not do anything else. I won’t do my toenails or my fingernails. I was terrible at dating because of what dating involves, the presentation of something”). Plus of course, her revelation of the greatest lie ever told (more of this later) and her brave stance in the face of male critics who reviewed her books.

If my stars had been kinder, I would have met Zadie Smith at the Department of Creative Writing, New York University, in 2010. But our paths were never destined to meet. As fate would have it, by the time she joined the faculty as a lecturer I had bid adieu to my graduate studies at NYU and returned home. Among all the contemporary writers that thronged the classrooms, escalators, cafes and streets around NYU, I so yearned to bump into Zadie (in her turban, thick-rimmed glasses and big trainers) because I found her alluring, not only as a novelist, but as an essayist and an advocate of the minimum-makeup movement (“When I was growing up,' she once said, “just the whole idea of being a girl — it seemed like a lot of work to me. Even now, I will wear lipstick and mascara but I will not do anything else. I won’t do my toenails or my fingernails. I was terrible at dating because of what dating involves, the presentation of something”). Plus of course, her revelation of the greatest lie ever told (more of this later) and her brave stance in the face of male critics who reviewed her books.

James Wood was one such critic. When he reviewed White Teeth, Zadie's debut novel, published when she was 24 which won many awards he accused her of writing about 'hysterical realism'. Zadie countered this by pointing out that particularly with girl writers male critics constantly wish to correct and improve. She said, “The way male critics write about women is part romantic, part corrective, part, ‘now listen young lady.’ And Zadie Smith was one writer who wouldn't have any of it lying down.

James Wood was one such critic. When he reviewed White Teeth, Zadie's debut novel, published when she was 24 which won many awards he accused her of writing about 'hysterical realism'. Zadie countered this by pointing out that particularly with girl writers male critics constantly wish to correct and improve. She said, “The way male critics write about women is part romantic, part corrective, part, ‘now listen young lady.’ And Zadie Smith was one writer who wouldn't have any of it lying down.

Author of four critically acclaimed novels – the first, White Teeth, which deals with the 50-year friendship between Archie, a working-class Londoner, and Samad, a Bengali Muslim, whose ill-fated affair with a white woman proves a catalyst for the novel's central events – Zadie Smith's latest work is Swing Time, which focuses on 'two brown girls who dream of being dancers'.

Not surprisingly as with White Tiger, this novel too is based in North West London which is where Zadie's first home was, on the opposite side of the same street in which she owns a house now, a pretty, low-rise council estate called Athelstan Gardens in North London. Her mother, Yvonne Bailey, had moved to London from Jamaica at the age of 15, and then married Harvey Smith, who was white, British and much older. They went on to have two boys, Ben and Luke and divorced when Zadie was a teenager – a studious girl and precocious author of sonorous words (at 14, around the time her mother gave her Zora Neale Hurston to read, she changed her name from Sadie to Zadie).

She read, more or less, for a living, or instead of one, and was the first person in her family to go to university. (In her second year, at Cambridge she published a story in a student anthology, and later met the boy who had edited it, Nick Laird. They married in King's College chapel in 2004.) 'My mind is novel-shaped,' she once said in an interview with the Guardian, by way of explaining the way her imagination was trained. Her mother was a library zealot, and her father an autodidact. 'Pretty much the only place my parents' marriage could be considered a match made in heaven,' she said recently, 'was on their bookshelves.' Smith claims she was a large child, and 'invisible', which was probably why she was so studious. 'That's the problem with pretty girls, they never get anything done.' To this day, what confidence she has stems from this: 'the belief that once you learn to read, nothing is beyond you in its essence'.

'It's so funny,' she recalled in a more recent interview also with the Guardian, 'Nabokov, who I loved more than any other writer when I was young, had such contempt for dialogue. When I was younger I never wrote a word of dialogue because of him. I thought it was a childish part of a novel. I wrote White Teeth kind of feeling ashamed all the time. But now I think it's one of the few places where you can try not to manipulate. You can't know what's going on in somebody's heart or head – but you can listen, and write down speech. It's not honest or dishonest, it's just… what there is.'

'It's so funny,' she recalled in a more recent interview also with the Guardian, 'Nabokov, who I loved more than any other writer when I was young, had such contempt for dialogue. When I was younger I never wrote a word of dialogue because of him. I thought it was a childish part of a novel. I wrote White Teeth kind of feeling ashamed all the time. But now I think it's one of the few places where you can try not to manipulate. You can't know what's going on in somebody's heart or head – but you can listen, and write down speech. It's not honest or dishonest, it's just… what there is.'

Adhering to this theory, offering few descriptions of her characters in her novels she implores the reader not to judge people on what they look like, and listen instead to what they say. There is a moment in Swing Time, for instance when a character makes her friends laugh because she has told a story many times and left out until the latest rendition what they consider to be a key detail: 'How could you not mention the headscarf!' they say. Zadie herself is doing something similar throughout her work.

'It's an existential point,' she explains. 'It's beyond politics. I decided the only race I was going to mention was white people, so anyone who's white is identified consistently. I suppose I want to show a world in which people who are not white are not determined by white people. And it proves to be incredibly hard to do that. You realize if you grow up black in England that to a lot of people here being black is in itself a political statement. But we're neutral to ourselves, you understand.'

Her own experience when it came to discrimination, she says, was always softened by her academic achievements, though she hints that this might have been through a desire to overcompensate in the face of prejudice. 'When I was little, we'd go on holiday to Devon, and there, if you're black and you go into a sweetshop, for instance, everyone turns and looks at you. So my instinct as a child was always to over-compensate by trying to behave three times as well as every other child in the shop, so they knew I wasn't going to take anything or hurt anyone. I think that instinct has spilled over into my writing in some ways, which is not something I like very much or want to continue.'

If Zadie has doubts about her abilities as a writer, she finds compensation in being part of a community of other writers. 'I think you have to be interested in literature in general, not just the stuff you happen to write,' she says. 'That's just one little window in a massive, extraordinary church.'

As with so many other women writers, the birth of her daughter Kit,inevitably, was life-altering for Zadie. 'Once you give birth you do feel a lot less scared of things. I was always so scared of everything. I think our generation had so much fear that it was all going to go horribly wrong, because we weren't taught about mothering, we were taught how to get an education,' she reflects. 'I was so surprised to find my daughter thought I was all right. I still can't get over it. She really likes me!'

She goes on to point out that the honest truth is that Eliot wrote without children, Woolf wrote without children, Gertrude Stein.. loads of people write extraordinary things without children. “Every life that you live will give material for fiction. But given that I do have children, it is that experience of just the simple thing of seeing life in the round. It’s so dull to say that, but it is extraordinary to see your childhood replayed, refracted, to see yourself saying things your parents said, to be in this new relation to death.”

Finally, to Zadie's revelation of the greatest lie ever told...about love. Any guesses? If you have read On Beauty you would already know… in case you haven't, why its simple really. According to Zadie, (and I think you will agree), 'the greatest lie ever told about love is that it sets you free.'

Add new comment